Situated on Joy Road in the Barton-McFarland neighborhoods of Detroit, the community retail networks project leveraged existing community skills and established an adaptive space centered on exchange. The architecture’s flexibility met community needs through tectonic assemblages, striking a balance between principles of discrete architecture and the opportunities offered from mass-produced components. Programmatically, the design incorporated areas varying in size and purposes to serve a range of merchant types. Spaces included areas for design, production, and gathering.

Exploring an architectural system that facilitates commerce in Detroit, MI

Courses | Arch 660: Thesis Development Seminar, Arch 662: Thesis Studio

Thesis advisor | Jose Sanchez

Timeline | August 2020 – May 2021

Location | Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan

Research

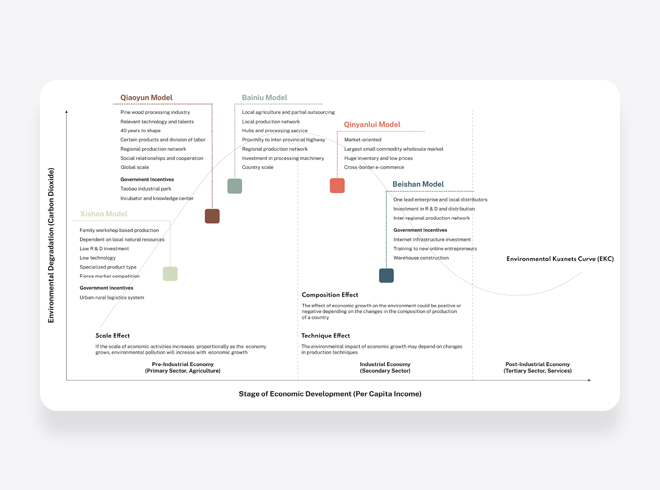

Economic development analysis

Secondary research on the economic structures of several different geographic regions introduced mechanisms that influenced the retail network in the Barton-McFarland neighborhood of Detroit, Michigan. In the Emilia Romagna region of Italy, cooperation drove entrepreneurial success. In rural China, technology provided economic opportunities that reduced poverty. In Shenzhen, an industrial past gave rise to a culture of open source. The night markets of Taipei displayed a spectrum of legal and extralegal merchant typologies.

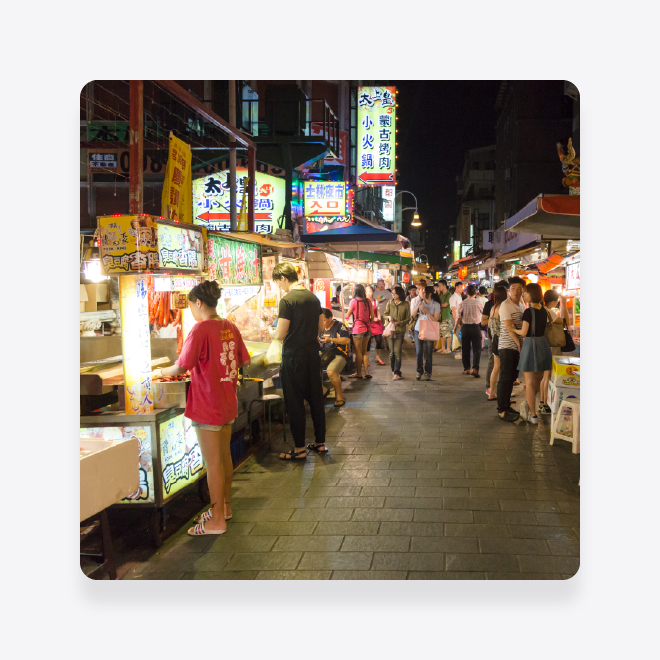

Taipei, Taiwan Night Markets

In “Rethinking Decentralized Managerialism in the Taipei Shilin Night Market,” Chihsin Chiu addressed the dynamics between self-management and private management of both legal and extralegal street vendors. This dynamic favored property owners over the vendors. While property owners paid association fees for the maintenance and upkeep of the night market, these fees were often passed down to the independent vendors, placing them under financial pressure.

Shi Lin Night Market. Shilin District, Taipei City, Taiwan. Photo: AsianDream/istockphoto.com

These vendors rented space from property owners when they met certain conditions. According to Chiu, an opportunity existed to reorient urban managerialism, allowing all parties to make placemaking decisions.1 The project emphasized collaboration to defend against short-term profit centers and to promote economic inclusivity between merchants and property owners. This approach also revealed how architecture responded to entrepreneurship.

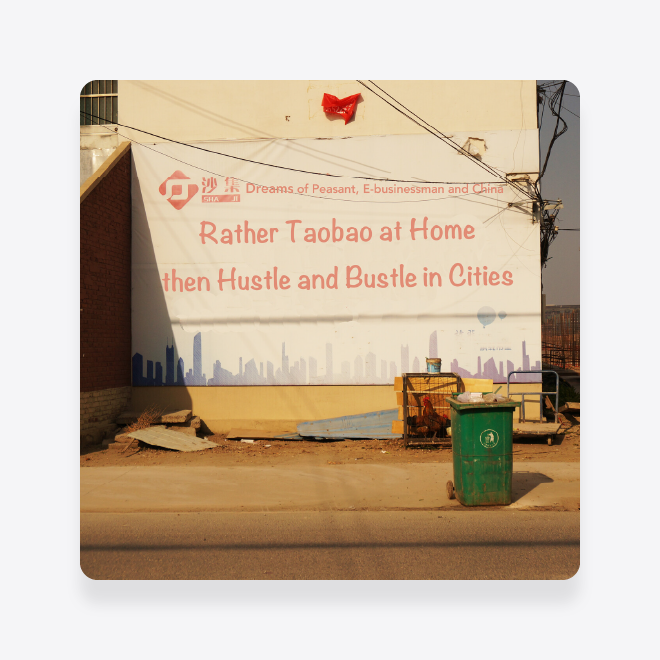

Taobao Villages, rural China

The latest Five Year Plan, which centered on poverty alleviation in rural China, introduced the concept of Taobao Villages. These villages harnessed the market forces of e-commerce and tapped into China’s expansive middle class to generate wealth in rural areas.

Prosperity Messaging. Dong Feng. Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China. Photo: Song Yu/AMO/CAFA

Through government investment, physical infrastructure in rural areas, including roads, water pipes, and electrical systems, improved. The same investment also enhanced the digital infrastructure of rural villages. However, despite significant government support, market forces interfered with the potential success of Taobao Villages. Competition based on cost drove revenues down and affected the quality of products made in the Taobao Villages.

Although market forces inevitably influenced the retail network, there was an opportunity to mitigate these effects by embracing economic development at the local level through architecture and technology. 2

View a full size version of the Taobao ecosystem diagram →

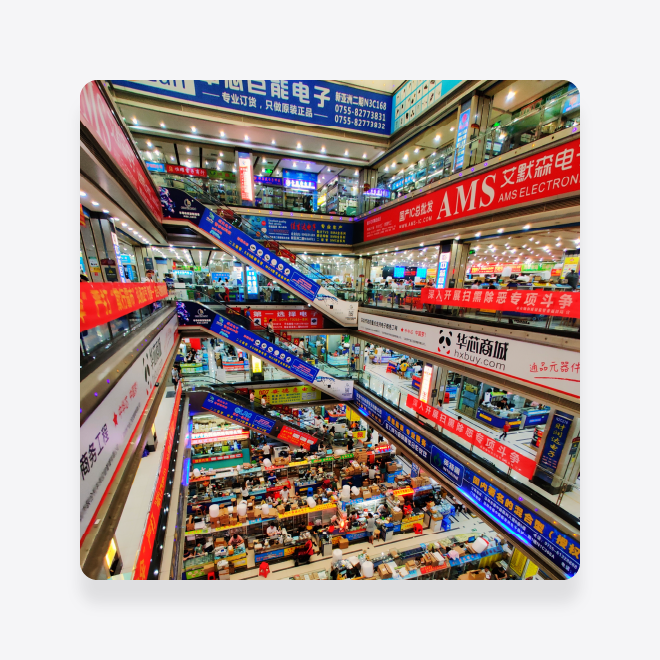

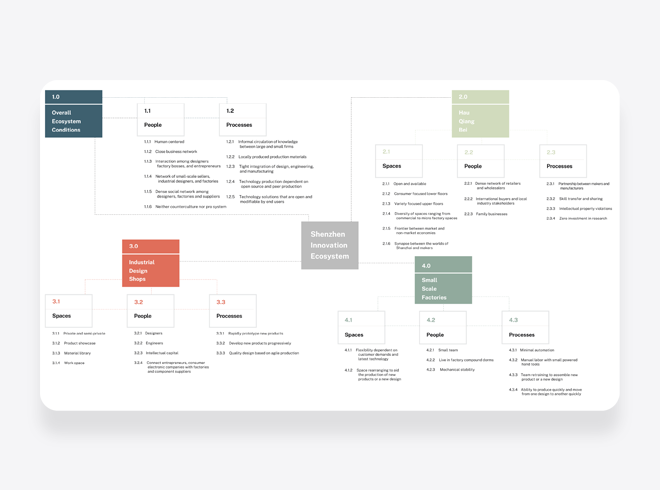

Shenzhen, China

Shenzhen grew rapidly after its designation as a special economic zone. As a strategy to alleviate poverty, the zone emphasized electronics manufacturing. Over time, conditions presented an opportunity for a collaborative technology ecosystem. This ecosystem showcased a diverse group of members, from small merchants to ambitious entrepreneurs.

Hua Qiang Bei Electronics Market. Futian, Guangdong, Shenzhen, China. Courtesy of maia crimew via unsplash.com

More importantly, the emphasis on open source collaboration helped sustain the ecosystem. For example, small merchants embraced collectivity by focusing on specific niches. Some merchants designed, others manufactured, and some sold.

Unfortunately, market forces began to affect this ecosystem. Gentrification started impacting the electronics malls where these small merchants earned their income. Since revenues were small, merchants moved when they couldn’t afford the rent. Additionally, government policy introduced issues of economic priorities.3

View a full size version of the Shenzhen ecosystem diagram →

Emilia -Romagna, Italy

The Emilia-Romagna region of Italy exemplifies a merchant network on a large scale. Here, small businesses and merchants found stability, flexibility, and resilience through cooperation. This network allowed these merchants to compete with larger firms while maintaining democracy.

Bologna, Emilia-Romagna, Courtesy of Cristiano Pinto via unsplash.com

Government support facilitated collective efforts as regional networks. More importantly, the ecosystem prioritized business operations that encouraged cooperation. Financial institutions, for instance, actively supported collectives, fostering both external and internal mutualism.

Continuing, the region focused on retail and automobile parts. This form of networking enabled nimbleness, allowing adjustments to market conditions and retaining the creativity of culture. Over time, the goal was to establish an ecological economy centered on producing energy, rather than just consuming it. 4

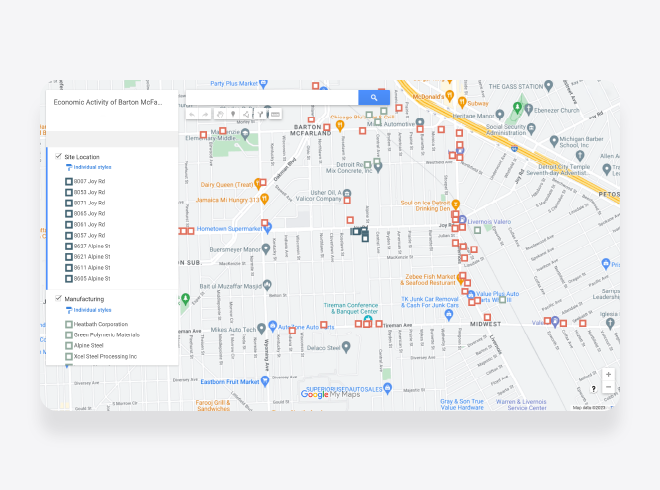

Barton-McFarland, Detroit, Michigan

Barton-McFarland is a neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan, with a population of 9,242. According to recent data, the median home value was $49,032, and the median rent was $967. At that time, 60% of the population owned their homes, and 40% rented.

In addition, residents of Barton-McFarland had a median household income of $36,381. Families with children made up 26% of the households. Regarding education levels among Barton-McFarland residents: 6% had a master’s degree or higher, 4% possessed a bachelor’s degree, 29% had attended some college or earned an associate’s degree, 39% held a high school diploma, and 22% had an education level below a high school diploma.

View the map of economic activity in Barton-McFarland, Detroit, Michigan →

Project goals

Goal one | Design a flexible discrete architectural system that is reconfigurable to demonstrate accommodations for distinct merchant types and activities.

Goal two | Incorporate at least three distinct methods of mobility access points into the site design.

Goal three | Conceptualize and design an application that introduces open-source components as a mechanism to facilitate knowledge sharing.

Architectural design

Site considerations

The City of Detroit owned several parcels on Joy Road in the Barton-McFarland neighborhood for the project site. Joy Road acts as a commercial thoroughfare, with residential neighborhoods flanking its north and south sides. The parcels in question faced east and west. Directly south of the site, some houses stood intact, while others showed signs of disrepair.

In addition, demolitions had left some homes as vacant lots. Similarly, a previous structure had once stood on the parcels but no longer did. The parcels came together to create a flat area, but overgrown vegetation covered the site, along with the ruins of the previous structure. At this time, the city zoned the parcels as commercial.

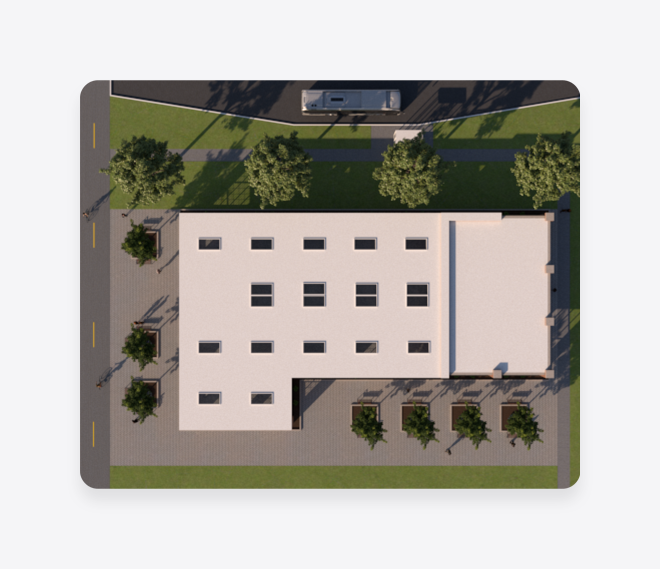

As the provided rendering shows, the parcels linked to the planned Joe Louis Greenway to the west of the site. Since Joy Road remains a main thoroughfare, the redesigned site included a bus stop. The redesign also revitalized the sidewalk, ensuring a connection to the homes to the south.

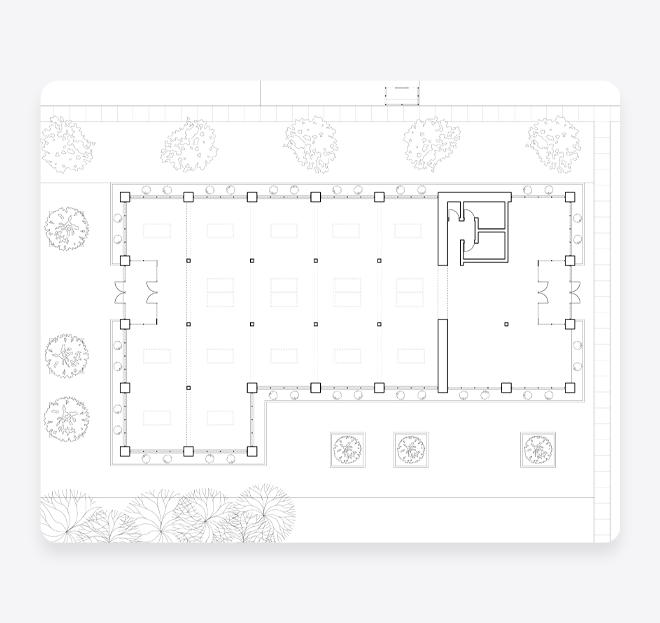

Site plan with first floor

The project’s form adhered to the dimensions of the original structure. Moreover, its design language drew inspiration from the era of Albert Kahn, the renowned American industrial architect based in Detroit, known for his significant work on automotive plant complexes.

The open layout included spaces for the adaptive structures detailed later in this case study. These flexible spaces gave merchants the versatility to adapt and reconfigure as their needs changed over time. The design integrated vestibules to create climate zones and shield the interior from the harsh Detroit winter. Rows of skylights dotted the ceiling of the flexible space, enhancing the ambiance with ample natural light.

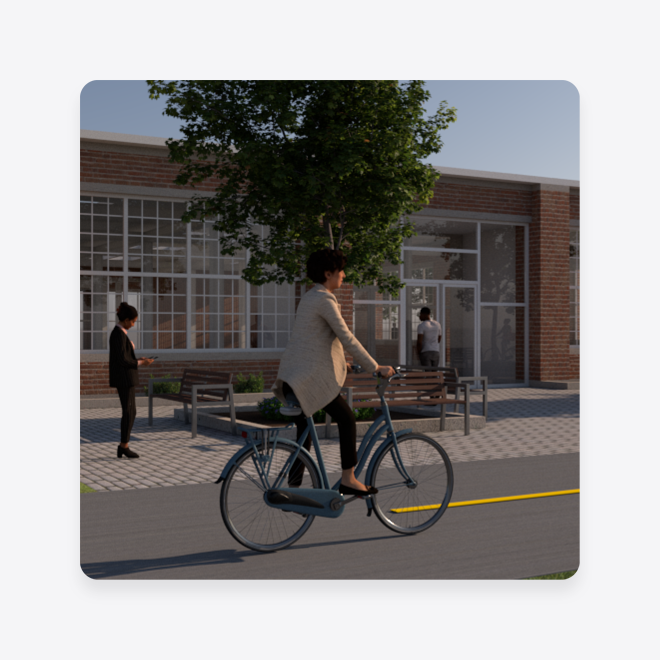

Perspectives

The initial perspective offered an eye-level view of the project’s west entrance. Several seating areas and landscaping elements punctuated this entrance. The brick exterior, complemented by stone accents and white mullions, preserved a connection to the human scale.

Another key feature that maintained the human scale was the streamlined roof, inspired by numerous projects undertaken by SANAA. SANAA is the renowned Japanese architecture firm founded by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa.

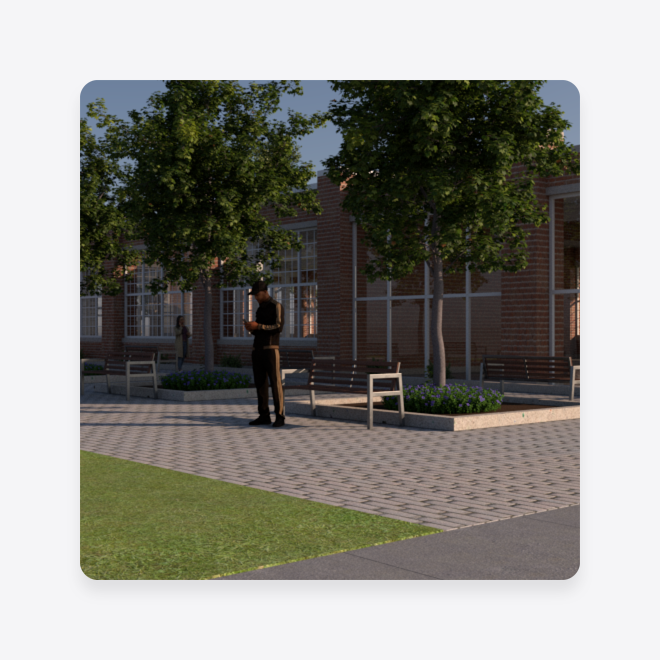

This perspective showcased the courtyard from an eye-level view. The courtyard served as a buffer from the homes on the south side of the site, acting as a bridge between the project’s commercial space and the adjacent homes.

Featuring multiple seating areas and lush vegetation, the courtyard space functioned as the project’s living room. Situated on the east side of the site, the urban courtyard neighbored the majority of homes.

The subsequent eye-level perspective showcased the east entrance. In a bid to retain the human scale, a series of expansive windows created a sense of airiness and openness.

The sidewalk, seamlessly integrated with its surroundings, fosters a continuous connection to the larger neighborhood. With a design intended to not only be functional but also sociable, this element aims to bolster community ties and encourage interactions throughout the area.

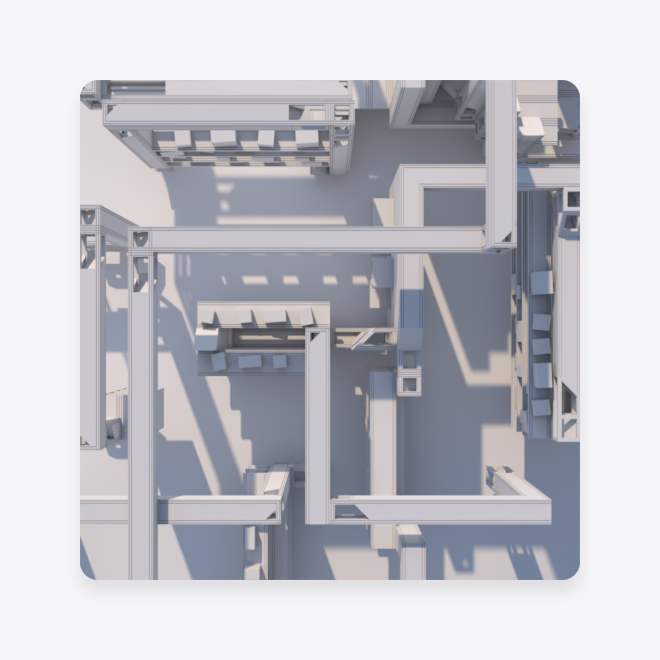

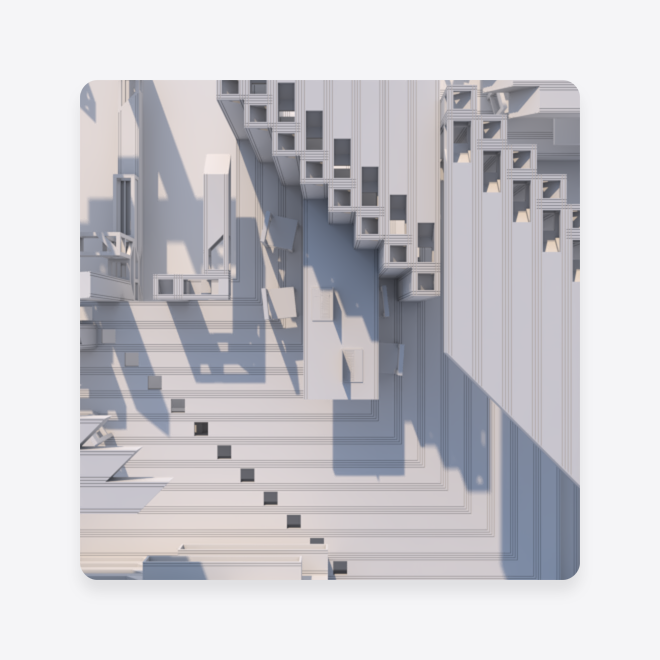

Assemblages

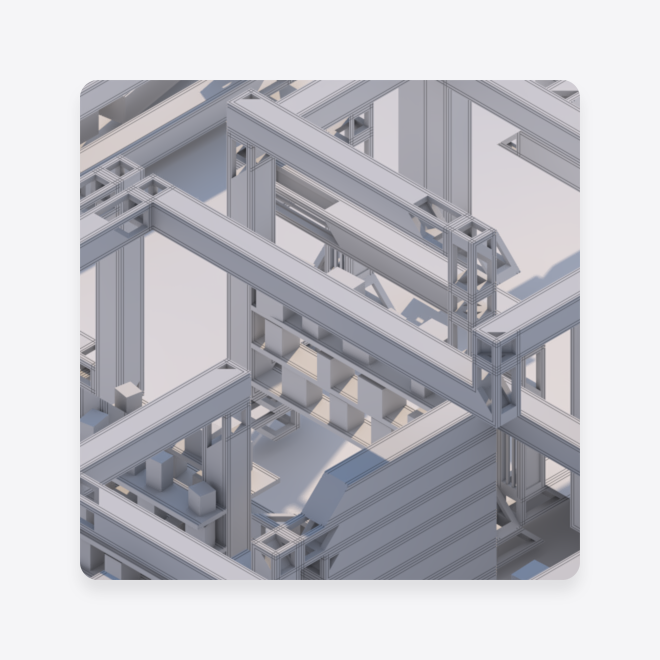

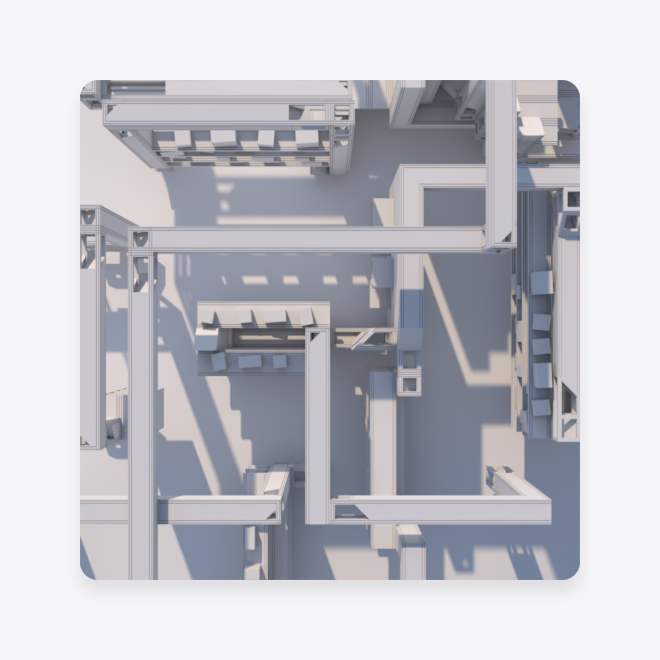

The floor plan of the space allowed merchants to create flexible areas. A bird’s-eye view of the project shows the various components used to shape and define space.

In this space, a workstation stood along a column group of components. Users mounted the tabletop to the components using standard hardware that fits t-slotted framing.

In this isometric view, the components formed an adaptable retail space suitable for accommodating larger items. These components provided the support structure for the retail shelving, which allowed easy addition or removal of shelving units as needed.

The isometric view revealed structural connections to other elements within the space. For instance, a wall of components served to delineate this area from another portion of the space.

From this bird’s-eye perspective, another adaptable retail space is evident. This larger area accommodated a wider variety of items available for purchase. As in the previous space, the components served as supports for the shelving units.

This perspective also demonstrated the versatility of the components in extending spaces. The assembled components created several different pathways that meander through the space, providing an engaging browsing experience.

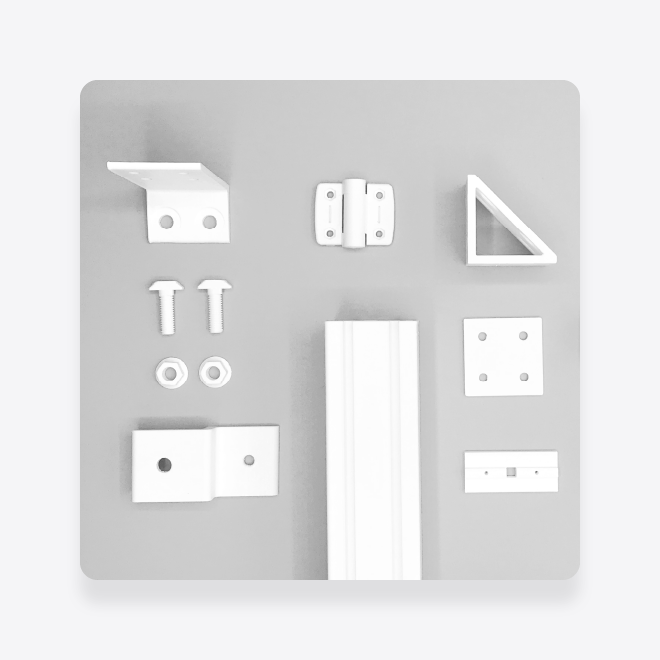

Primary components

The primary components of the project formed the structural elements of the adaptive merchant spaces. Because of the flexibility evident in the floor plan, merchants could assemble and disassemble their spaces as needed without assistance.

Due to the t-slotted rails positioned at each corner, users modified the components to meet space needs. This capability also let users customize secondary components when they created spaces.

Secondary components

The secondary components followed design patterns contained in mass-produced fittings for t-slotted framing. This provided the opportunity for individuals to create custom brackets and elements following a fabrication framework.

The implementation of secondary components also mitigated potential issues with accessibility for custom hardware in adaptive spaces.

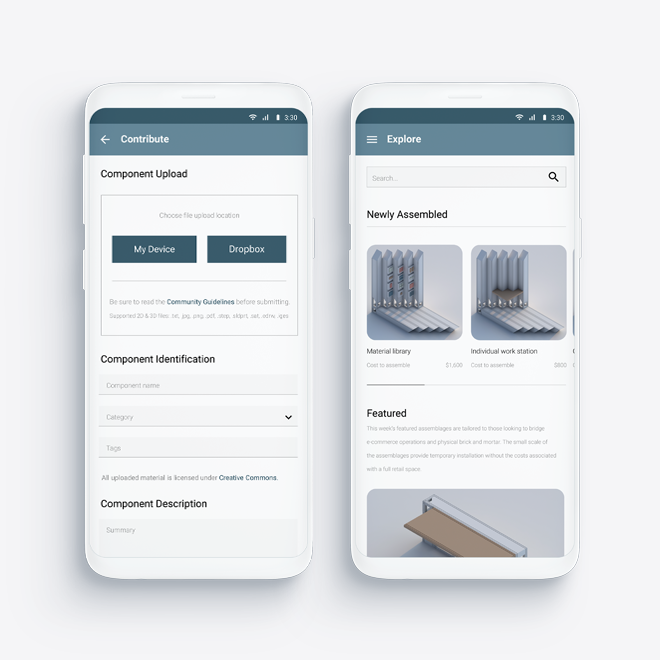

Consumer-to-consumer platform

The consumer-to-consumer platform allowed merchants to connect and share ideas. While the platform promoted knowledge sharing within the surrounding area, it also extended beyond it. Merchants achieved this by uploading and remixing component and assemblage designs.

The application allowed users to browse designs, view associated costs, and receive estimates on do-it-yourself construction time.

References

1 Chiu, Chihsin. “Rethinking Decentralized Managerialism in the Taipei Shilin Night Market.” Management Research and Practice 6, no. 3 (09, 2014): 66-87. https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.

umich. edu/docview/1560657783?accountid=14667.

2 Wired UK. “Shenzhen: The Silicon Valley of Hardware.” YouTube video, 1:07:50. July, 5,2016. https://youtu.be/SGJ5cZnoodY

3 Petermann, Stephan. “Villages with Chinese Characteristics.” Countryside, A Report. 124-127. Koolhaas, Rem, Richard Armstrong, Troy Conrad Therrien, Julius Wiedemann, and Meike Niessen. Köln: TASCHEN, 2020.

4 Young, Melissa, and Mark Dworkin. WEconomics: Italy. Reading, PA: Bullfrog Films, 2016. http://docuseek2.com/bf-wecoi. Films.